As Chinese labor shortages continue to be a source of woe and materials and shipping costs skyrocket, domestic manufacturers flaunt their stateside addresses, answering both logistical needs and an increasing demand for made-in-the-U.S.A. merchandise. By Lyndsay McGregor When Ruth True opened her specialty shop NuBe Green in 2009, the Seattle, WA-based retailer had to dig […]

- Adore La Vie

- NuBe Green in Seattle, WA

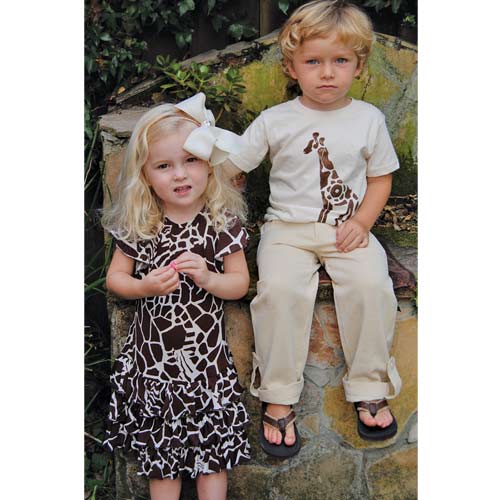

- Fiveloaves Twofish

- TwirlyGirl

- Barley & Birch

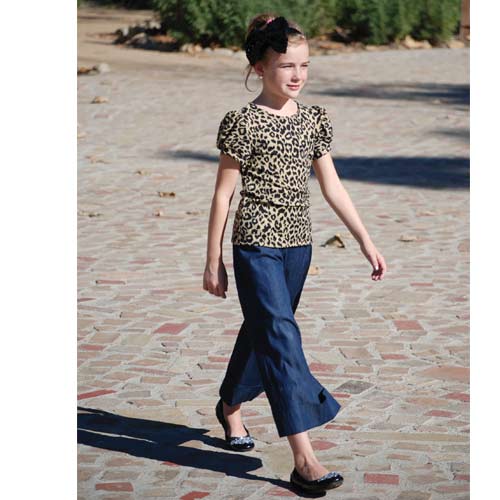

- CPC Designs

- Neve/Hawk

- Born in the U.S.A. – Winter Water Factory

As Chinese labor shortages continue to be a source of woe and materials and shipping costs skyrocket, domestic manufacturers flaunt their stateside addresses, answering both logistical needs and an increasing demand for made-in-the-U.S.A. merchandise. By Lyndsay McGregor

When Ruth True opened her specialty shop NuBe Green in 2009, the Seattle, WA-based retailer had to dig for American-made stock. Just three short years later, an increasing number of homegrown brands are knocking on her door in an effort to gain precious shelf space amid her store’s exclusively made-in-the-U.S.A. merchandise mix that includes kids’ clothes (from the likes of Little Orange Room, Jenny Jo and Trash-A-Porter), furniture crafted from local storm-salvaged trees, jewelry fashioned from recycled metals, bags and wallets made from repurposed bicycle inner tubes and tabletop and glassware from post-consumer bottles.

The store’s success mirrors the locavore philosophy sweeping the United States, a trend that took hold in part because of the recent recession and rising unemployment. “It’s hard to keep politics out of it,” says Stefanie Lynen, the Brooklyn, NY-based designer of Winter Water Factory. “All the money that I pay to make my product is paid to people who live in the community. They pay taxes on it and keep jobs here and money here and that gets reinvested in the community,” she says. Heather Haas of California-based brand Fiveloaves Twofish agrees: “We take pride in the fact that we’re keeping [San Diego’s cutting and sewing community] alive…if we can help another American keep a job, that’s a plus,” she says. Kris Galmarini, designer of Charleston, SC-based Neve/Hawk, thinks the uptick in cost is something consumers are willing to absorb—so long as the quality is there. “They know the advantages for our economy,” she says. “People are willing to spend that extra dollar in order to support that.”

Even if domestic production is more expensive, for both buyers and manufacturers, supporting the U.S. labor force and American-made products seems like the right thing to do. “At the end of the day, everyone who makes and touches our clothing goes home and has a meal,” says Kit Kuriakose, Haas’ business partner. It’s a sentiment shared by Gaby Evers, one-third of the design team behind Pennsylvania’s CPC Designs: “A really interesting by-product of working locally is that you get to see the benefits of doing business with local businesses. The people in the factories have all met our kids. We see the people that are making our goods and we know that we’re helping to support them and their families and that’s a really nice thing,” she notes.

But it’s not just patriotism and community-awareness that’s fueling interest in local manufacturing. Ironically, one of the biggest factors contributing to the rebirth of American-made apparel has to do with China’s sourcing issues that are forcing manufacturers to look elsewhere for production, be it the U.S., India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia or Colombia, among others countries. The shift is backed by a Commerce Department’s Office for Textiles and Apparel report released in April, which found that apparel and textile shipments from China, the top supplier to the U.S., fell 12.7 percent in February to 1.6 billion SME compared with a year earlier. A report by the California Fashion Association says Chinese wages are rising due to a shrinking workforce caused by China’s “One Child” policy and also notes that apparel workers are going into other Chinese industries that offer better pay, hours and working conditions. That, plus increased shipping costs and problems with quality, has prompted manufacturers to look closer to home.

So, an industry that was once pretty much left for dead in the U.S. is showing a pulse. And, according to some manufacturers, it’s an easier endeavor than making goods overseas. Keeping control of the end product is relatively simple when the whole manufacturing process takes place down the road. “I didn’t want to go overseas and have to deal with imports and mistakes; all it takes is one mistake and you could lose your whole selling season or production season,” says Amanda Boyd of San Francisco, CA’s Adore La Vie. “I’m very fortunate to have everything at my fingertips.”

Quality Control

The convergence of American-made and higher quality is a battle cry heard from most local manufacturers sharing shelf space with their foreign counterparts. Incentives and payment systems overseas favor fast pace over high quality. Boyd notes, “My factory pays its workers an hourly wage; it’s not just trying to pump out numbers,” she says. “Overseas, factories pay per garment so workers might try to do 100 garments in an hour and the quality might be bad.”

But to some it’s the quality rather than the “Made in U.S.A.” pedigree that makes a difference on the shelf. A really well-made garment—one that is truly built to last—is deemed a worthy investment among consumers who demand more bang for their buck. “To be completely honest, we see people purchase our garments because the quality is amazing and, for the most part, because the designs are cute,” says Kyle Smitley, owner and founder of organic clothing line Barley & Birch. “That we’re U.S.-made is an added bonus.” Her collection of tees and one-pieces are made from 100 percent organic cotton grown in North Carolina and Texas and printed with water-based inks. “Our choice to be made in the U.S. was never a sales pitch; it was always what we thought a responsible company would do,” she reveals.

But manufacturing stateside also has perks for buyers looking for flexibility and speed in the fast-paced fashion scene. Not only does Evers, whose company works with two factories in Pennsylvania—a cutting room in Huntington Valley and production in northeast Philadelphia—get to see every single piece before it goes out, she’s able to turn around orders swiftly. “Customers are demanding. We can deliver faster than companies that are overseas. Retailers re-order consistently with us into every season. They’ll place their orders well in advance but once the season starts and they know our stuff is going to sell, they re-order and we’re able to get them goods in three to four weeks,” she says.

Cynthia Jamin, CEO and designer of handmade L.A. brand TwirlyGirl, adds that quick shipping and low minimums mean that they can be responsive to buyers’ needs: “We directly impact the buyer’s bottom line. They don’t have to keep a ton of inventory and order six months out thereby [positively impacting] their cash flow.”

The Road Ahead

One of the challenges now facing domestic manufacturing is how to manage growth. “If we have a small group investing a bit more in supporting U.S. suppliers right now, it will become more affordable for everyone down the road,” says NuBe Green’s visual director, Anne Fenton. Where that investment goes is a matter of debate. Whereas Neve/Hawk owner Galmarini envisions, “more streamlined factories and more things set up like there are overseas, where you go to one place and they help you with everything, from the pattern all the way through to production,” the Fiveloaves Twofish team would rather keep the vendors diverse, opting for a free-market model. “Socialized fashion, as I call it, when it’s under one roof, is a set price. You’re employing one person so one person is getting that whole entire contract,” Haas notes. “But when you have your vendors, you go to your jersey shop, you go to your button guy, etc. The button guy has to compete with the other button guys. It’s more of a capitalistic point of view and more people get to be employed.” Either way, a deeper talent pool in apparel manufacturing in the U.S.—from cotton growers to sewers and patternmakers—could help ensure the industry returns in a viable way.

“It would be great for everybody, from the kids coming out of college to those with the skill set that have been around for years. There’s plenty of space in certain areas of the country to put up dye mills and stuff like that and I think it would help with the prices,” Boyd says. “I think if each factory had larger quantities of us to produce for, the prices would go down a little bit. It would be easier on me and I could reduce my prices a little bit for the buyer who in turn could reduce his or hers for the consumers.”

Leave a Comment: